MONTREAL – Here at the Montreal Grand Prix, all eyes are on the drivers, but there’s far more to it than just who’s behind the wheel. It’s the engineers behind the car that also make the difference between winning and losing.

That’s the point of the Infiniti Engineering Academy, a global competition to find seven of the world’s best engineering students for the opportunity of a lifetime. This year’s Canadian winner, 23-year-old Matthew Crossan of London, Ontario, will now spend a year in England. Six months will be spent working alongside engineers with the Renault Sport Formula 1 team, and the other six at the Infiniti Technical Centre working on road vehicles.

The showroom at Luciani Infiniti is ready for the race.

The showroom at Luciani Infiniti is ready for the race.

While those two may seem at odds with each other, many consumer vehicle technologies come from racing. Such things as lightweight materials, energy recovery, and even better tires trace their origin to the track, and Infiniti takes advantage within the Renault-Nissan Alliance for these trickle-down technologies.

The Engineering Academy is now in its fourth year. It’s the second time Canada has competed, and last year, Felix Lamy of Gatineau, Quebec, was the winner. He’s currently working with MATLAB simulation software on suspension and dynamic performance. It’s used to determine lap times in racing, while on consumer cars, it helps with the vehicle’s handling and safety performance.

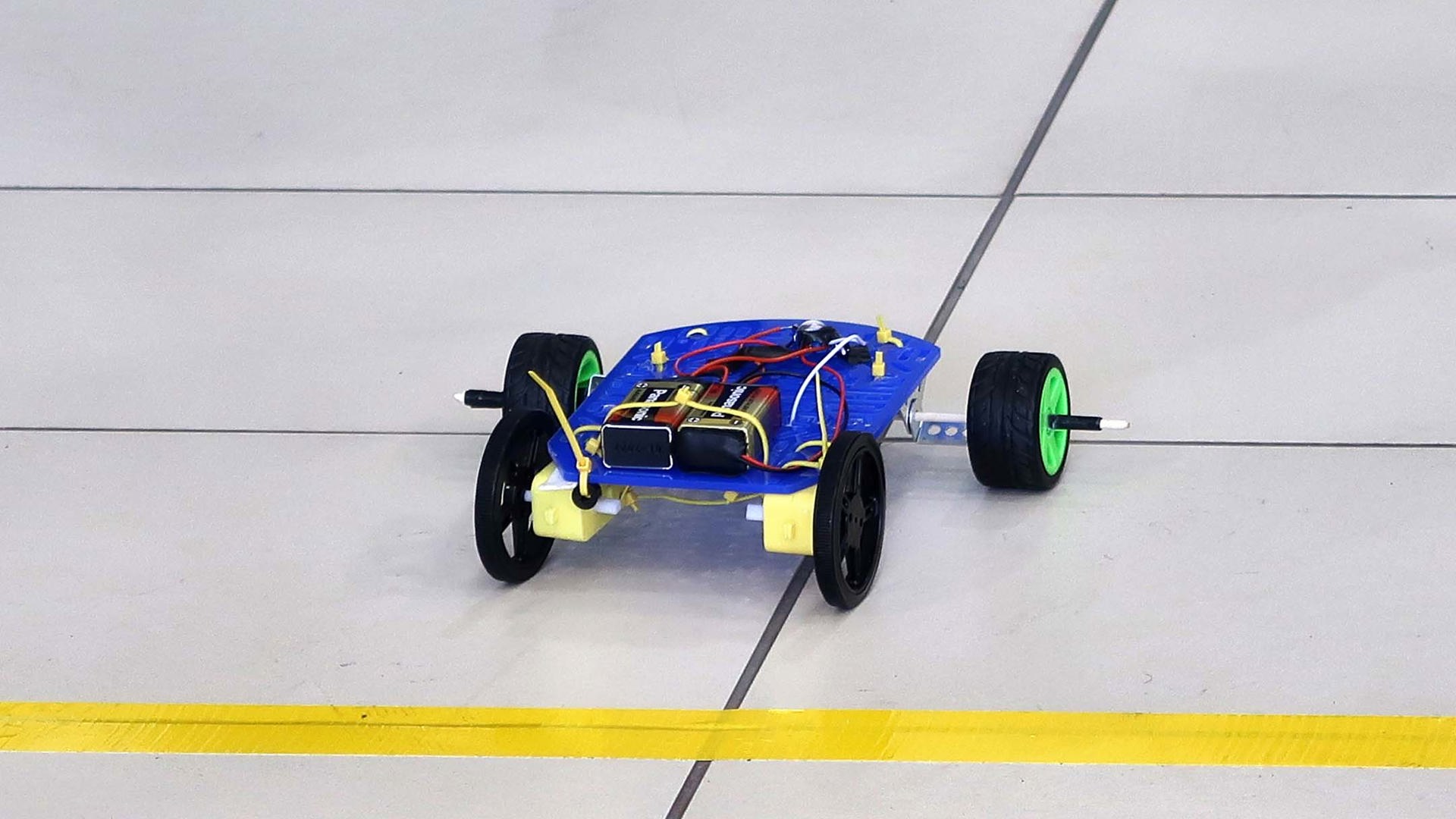

A team puts together a model car, which will be raced as part of the challenge.

A team puts together a model car, which will be raced as part of the challenge.

Ten finalists compete in the two-day test, and it’s taken a lot to get here. Across Canada, 341 students applied online. A British recruitment company makes the first cuts, according to Jonathan Bowers, project manager for the Engineering Academy. “The students are asked personality questions, given some brain teasers and problems, and they upload their résumés,” he says. “They pick the top one hundred or so in each country to do Skype interviews, and based on that, they select the ones to go forward.” Specific engineering specialties aren’t required, because the automaker needs top talent on every aspect.

Engineers must work together, and so along with their individual merits, students are scored on teamwork. Even the brightest competitor won’t take the top spot if he or she can’t collaborate to solve problems. The seven global students won’t work as a team in the technical centres, but they share housing.

Samantha Flavel with her team's car.

Samantha Flavel with her team's car.

“Infiniti is a diverse company,” says Tommaso Volpe, global director for Infiniti Motorsports. “Formula 1 is the pinnacle of racing, but it doesn’t take advantage of world talent like it should. Few of the engineers are from outside Europe. They can’t get Canada and the US, or Mexico, or China, but we can. Our mission is to show that this diversity of talent can bring a lot of innovation to Infiniti and to Formula 1.”

In its first year, the Infiniti Engineering Academy drew 1,500 applications worldwide. This year, the seven global winners were chosen from 12,000 across 41 countries.

As one of the engineering challenges, the teams had to build race cars from piles of parts, and then successfully run them on a "drag strip".

As one of the engineering challenges, the teams had to build race cars from piles of parts, and then successfully run them on a "drag strip".

In Canada, the finalists were Antonio Badea, who studies at Concordia University in Montreal; Matthew Crossan, at Western University; Jackson Diebel at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario; Andrei Dragos at the University of Calgary; Samantha Flavel at Carleton University in Ottawa; Anthony-Jonathan Hokayem at the University of Ottawa; Mathew Marzanek of Queens University in Kingston, Ontario; Jason Soares at École Polytechnique de Montréal; Garrett Thompson at Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, Ontario; and Shaymus Veinotte at Dalhousie University in Halifax.

They all met right before the first day of challenges and quickly had to bond. Over the next two days, their tasks included individual exams, and pairing up to develop a Microsoft program. Finally, divided into two teams, they had to turn mounds of parts into model cars for a drag race.

They were assessed by Stephen Lester, managing director of Infiniti Canada; Andy Todd, director of Infiniti’s body engineering in the UK; and Charlie Martin, chassis engineer for Renault’s motorsports team. They also faced questions from a group of auto writers, who scored the finalists on their speaking ability. In addition to technical skill, they were judged on confidence, eloquence, passion, and their clarity in communicating ideas.

All of this year's competitors, with Nico Hulkenberg and 2016 winner Felix Lamy.

All of this year's competitors, with Nico Hulkenberg and 2016 winner Felix Lamy.

When it was all over, Renault Sport F1 driver Nico Hülkenberg made a surprise appearance to announce that Crossan, a Masters of Engineering Science student specializing in composite materials, was the judges’ choice. We in the media seats suspected he’d be high in the standings, and while all the competitors were top-notch, he almost naturally assumed the lead on the model-car team but drew in his teammates, insisted on their input, and when their car went sideways on its initial run, pulled them all in to come up with the solution that put them ahead at the finish line.

“I thought I was a strong candidate, but it was a very stiff competition, and I had no clue who would win,” Crossan says. “I think it’s because I showed consistency throughout the challenges. I wasn’t necessarily the strongest in each one, but I stayed consistent and persevered through the technical difficulties.

Matthew Crossan, the 2017 winner, and Felix Lamy, the 2016 champion, with Nico Hulkenberg.

Matthew Crossan, the 2017 winner, and Felix Lamy, the 2016 champion, with Nico Hulkenberg.

“This will be life-changing. I’ve been in school my entire life. I’ve never had an internship, just a couple of summer jobs, and now I’m with a major automotive company at the pinnacle of motorsports. If the path allows me, I’d like the dream of many engineers – to be in a technical director role. I like to see how everything goes together, not specializing in a single system on the car, but the cohesiveness of the entire system.”

The one-year placement includes a salary, but isn’t intended as a substitute for a university program, and the global winners continue their schooling once they’re finished.

With any luck, Matthew Crossan will ultimately achieve his goal, improving both the cars that run at events such as the Montreal Grand Prix, and the vehicles you’ll see on the showroom floor.