It’s annoying and potentially dangerous to get a flat tire, and while tires have improved immensely over the years, it’s still possible to pick up the nail that will ruin your day. So what’s a motorist to do?

There are some options, and the best-known are run-flat tires and self-sealing tires. Naturally, each has its good and bad points, and you should know the score before you plunk down your cash.

The idea behind both is that you can continue driving even when your tire has been punctured, but they’re completely different in how they do this. Run-flat tires will lose some or all of their air if they’re punctured, but they still support the vehicle. Self-sealing tires plug up the hole after a puncture, so the air inside doesn’t escape.

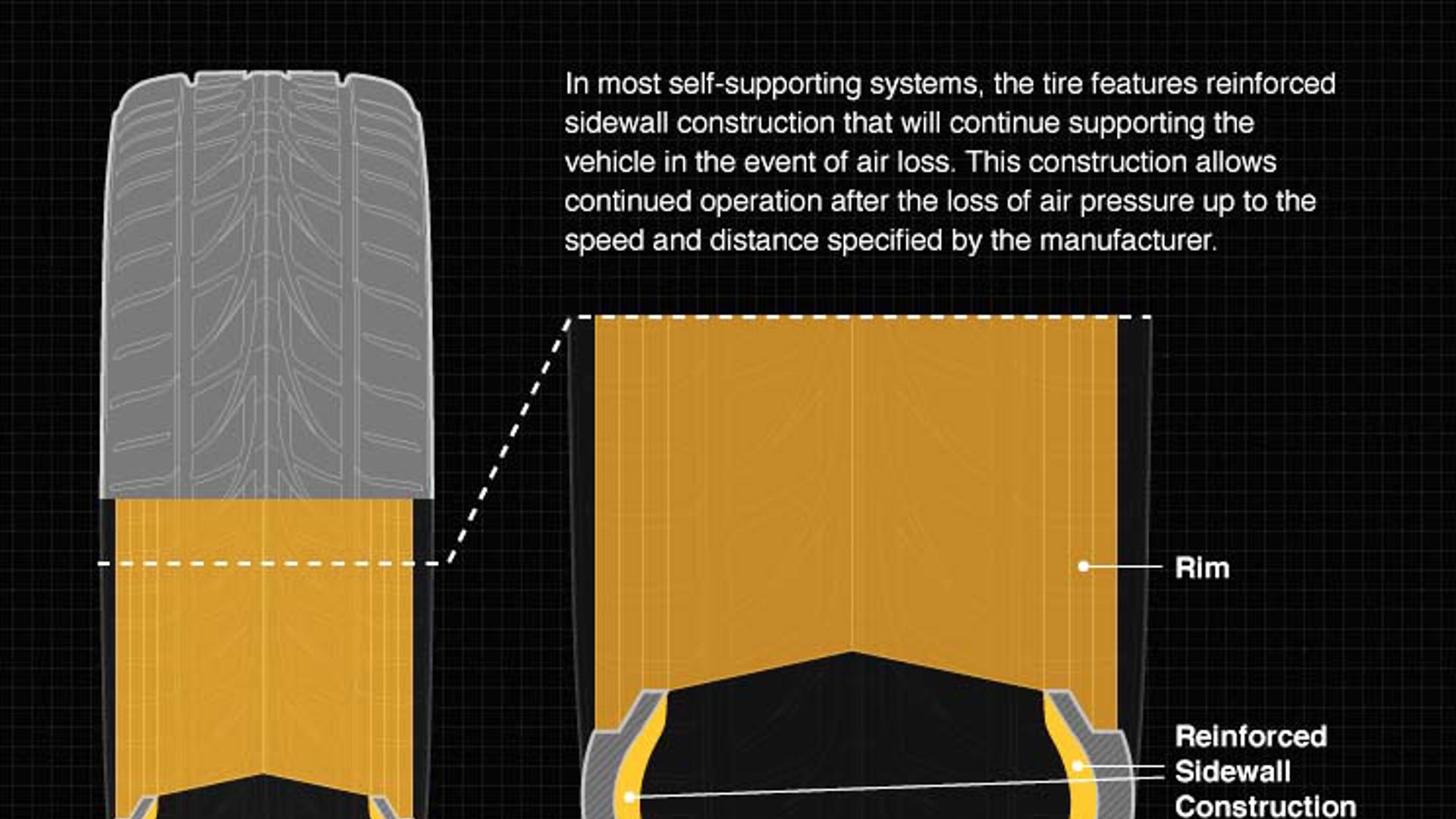

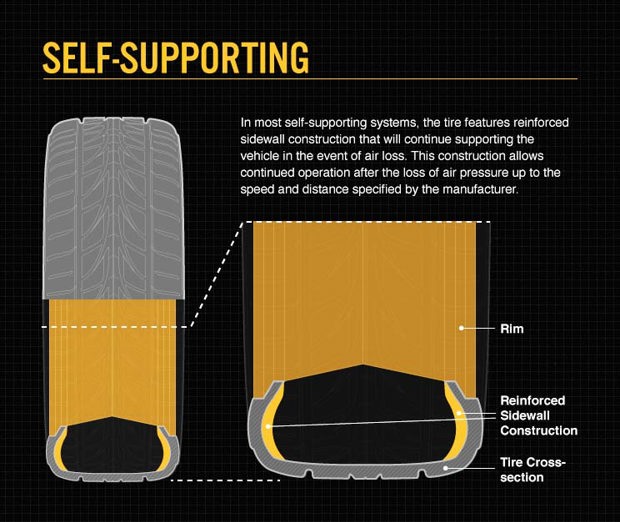

Most run-flat tires use one of two technologies. Self-supporting run-flats have a very stiff, reinforced sidewall. If the tire loses air, the sidewall stays on the rim and holds up the vehicle. This is the most common type of run-flat.

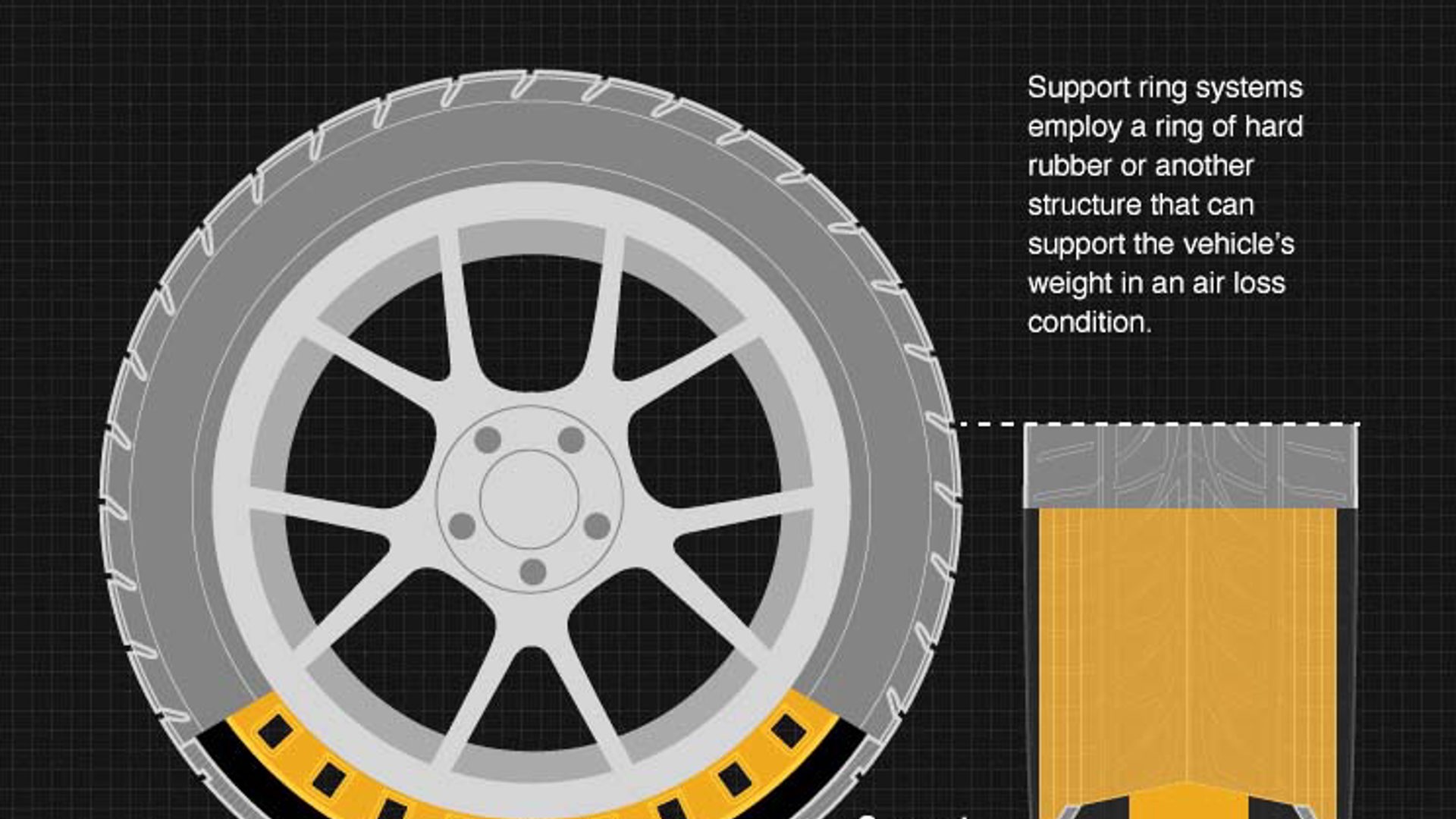

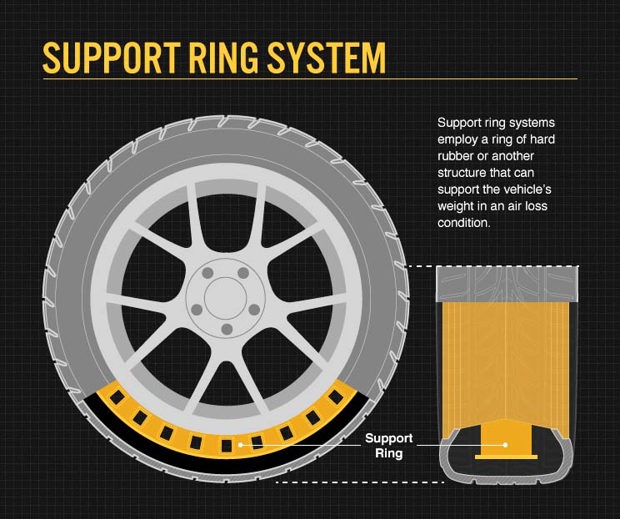

Support ring run-flats have a thick ring, made of hard rubber or other firm material, which encircles the inside of the rim. If the tire loses air, the ring supports the vehicle as you drive.

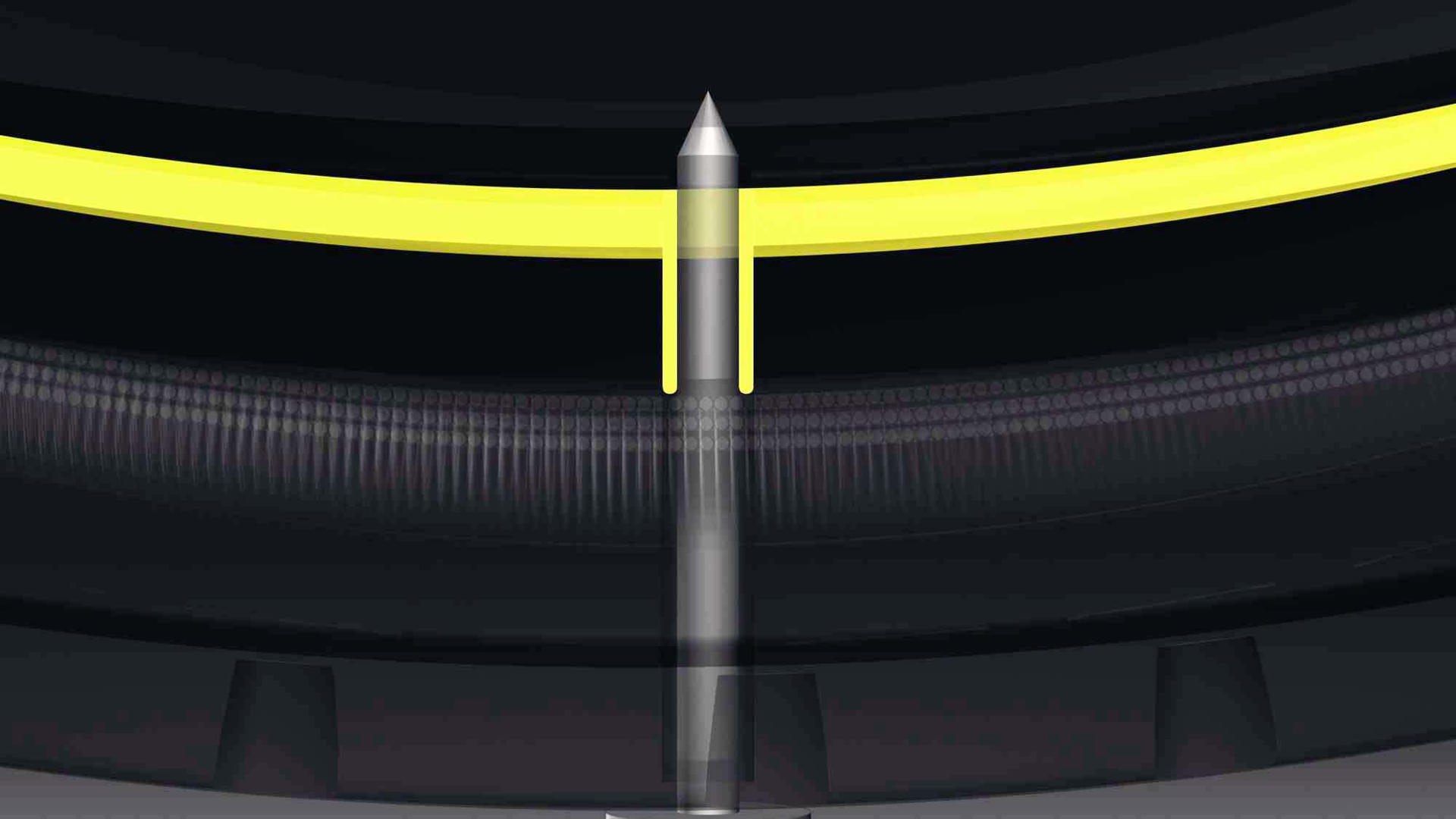

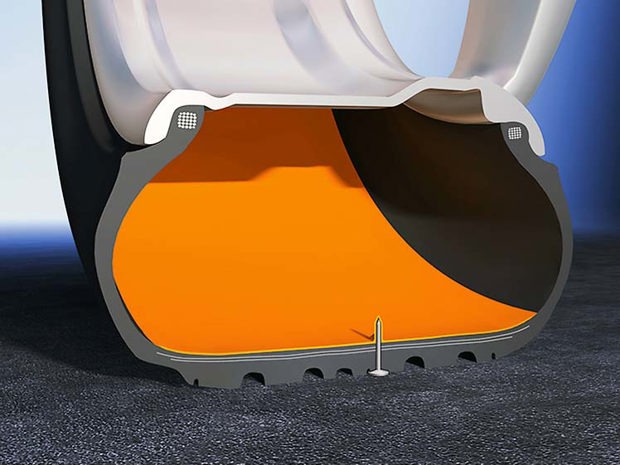

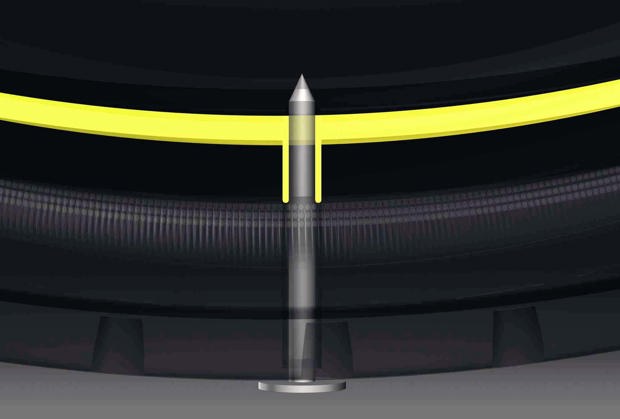

Self-sealing tires use a different approach. They contain an inner layer of sealant material along the tread. If a nail or other foreign object punctures the tire, the sealant layer closes the hole to prevent the air from escaping, and the tire stays inflated.

Both run-flats and self-sealers are all about the tread. A cut in the sidewall will compromise a self-supporting run-flat tire’s ability to hold up the vehicle. Self-sealing tires don’t have a sealant layer in the sidewall, and they can only handle punctures up to a certain size in the tread.

What’s good about run-flat tires…

- Manufacturers like them because they eliminate the need for a spare, which in turn shaves off weight in the name of better fuel efficiency. (That said, run-flat tires themselves are heavy because of their beefier construction, and they cut into the weight savings a bit.)

- Because there’s no spare tire, the space it would normally take up can be used for storage.

- If you get a flat tire, you don’t have to stop. Flats are never convenient, but they can be dangerous if you’re stuck on the side of a busy highway, or in an area where you may have to worry about your personal safety.

- Run-flat tires are also far more stable when they lose air. With a regular tire, a blowout can have a nasty effect on the vehicle’s handling.

- They can handle a larger puncture than a self-sealing tire and still remain driveable.

What’s bad about run-flat tires…

- The stiff sidewall that supports a run-flat tire doesn’t have much spring in its step. Rather than dissipate energy along rough roads, it transmits it into the cabin. While run-flats are much better today than when they first came out in the 1980s, they can still produce a very firm, harsh ride.

- Most of them require a special rim to hold them on. In the case of ring-support tires, the rim has to be fitted with the ring.

- They must be used with a tire pressure monitoring system (TPMS), since they don’t look different when they’re low on air. While most run-flats are original equipment on performance vehicles, Bridgestone makes one, called DriveGuard, intended for mainstream models such as the Toyota Corolla, Volkswagen Jetta, Honda Civic and similar vehicles that weren’t factory-equipped with run-flats. However, DriveGuard, isn’t recommended on a car that doesn’t have a monitoring system, which is mandatory equipment on all new cars sold in the US, but not in Canada.

- The longer you drive on them, the more likely they’ll be unrepairable. They run hotter when they’re low on air, and this can damage their inner layers. Manufacturers recommend that before fixing a puncture, the technician should dismount the tire and inspect the interior to be sure it can be saved. If it can’t, that brings us to the next point…

- They’re usually much costlier than conventional tires. Tire stores seldom carry a full range, and you could wait a while to get a replacement – not a fun proposition if you’re on a trip far from home.

What’s good about self-sealing tires…

- The sealant is just a layer inside a conventional tire, and the ride is not affected.

- While a tire pressure monitoring system is useful, self-sealing tires can be used on vehicles that aren’t equipped with TPMS.

- They don’t require a specialized rim, or special equipment to mount them.

- You can mix them with conventional tires on a vehicle.

What’s bad about self-sealing tires…

- There aren’t many downsides to self-sealing tires. There is a limit to the size of nail or screw puncture that the tire can handle, usually about 5 millimetres in diameter, and ideally near the middle of the tread. The sealant layer is not for deep cuts across the tread, or cuts or punctures in the sidewall.

- While the tire can close the puncture wound and prevent air loss, the tire should still be examined and repaired if necessary.

- The technology still isn’t that common among many tire companies. You may be limited in the brands and sizes available, and you might not be able to shop around for bargains.

- While they won’t take as much out of your wallet as a run-flat, they’re still more expensive than a regular tire.

One more option…

Even if your car doesn’t have run-flat tires, you may still open the trunk and find there’s no spare. In that effort to shed weight, some manufacturers give you conventional tires, along with a can of sealant that you spritz into the tire to plug up the hole, and an air pump that you plug into the car’s power outlet and use to inflate the tire.

When you take the tire in for repair, be sure to tell the technician that the tire’s been treated with goop. Sealant has a shelf life, so periodically check the date on the can, and if necessary, replace it with a new one. Tires never pick a good place or time to go flat, and you’ll thank yourself that you did.